Our Verdict

Opus: Echo of Starsong has many layers of narrative combined with numerous game mechanics, and it manages to make them all feel vital. Most importantly, though, its heartfelt story is one I will never forget, told in the perfect way.

Remember when EA asked, “can a computer make you cry?” Well, I don’t, I was minus-fifteen years old. The original advert was in 1983, and EA’s answer was “right now, no one knows.” Maybe that was true back then, but it definitely isn’t true now. It’s a question that gets made fun of – even though the original advert is quite sincerely lovely – because videogames have proved multiple times over the last thirty years that yes, a computer can make you cry.

That’s not because of the computer, though, it’s because of the creator. The human input into a videogame – the love, care, and attention – is what lets us connect in a way that can have us balling. You can feel that love, care, and attention from developer Sigono, as it intertwines with almost every aspect of Opus: Echo of Starsong.

Sigono is a Taiwanese indie developer that has made three games in the Opus series. Echo of Starsong is the culmination of years of work towards creating an engaging narrative game, mainly told through text, and intertwined with numerous mechanics. It’s sublime from beginning to end.

It’s set in some distant or alternate future where a handful of spacefaring civilisations explore Thousand Peaks for a resource known as lumen. Lumen is vital to everyone’s day-to-day among the stars, not just being connected to the creation of life, but also acting as a profitable resource akin to oil. This obsession with lumen is at the centre of everything in Thousand Peaks, whether it’s the history of conflict through the planetary system or how the protagonists’ stories progress.

The game opens with an old man, voice quivering, walking through a dilapidated cave. This is Jun, our narrator, retelling the story of his life, which we then get to play through. Everything in the story relates back to him 66 years in the future retelling his tale, from item descriptions to him saying ‘no, that’s not right,’ whenever you die.

This fragile old man’s voice is coated in melancholy, and so too is the whole of Echo of Starsong. It’s by no means a miserable game, but this man’s sadness and regret permeate every inch of the world. Just reading a seemingly inane item description can end with a heartbreaking but throwaway thought about his past.

His past starts for us with him hunting for lumen, having insulted one of the clan masters and having to run away. He vows to find lumen caves and help his clan become prosperous again. He meets a woman, Eda, who is about to buy dodgy intel about a lumen cave, so Jun wades in, and from there we have our two protagonists. There’s also Remi, Eda’s pilot aboard the ship the Red Chamber, who plays a vital role in the way everything progresses.

After a good chunk of backstory, the game starts. Because of certain events, Jun is now aboard the Red Chamber, helping Eda and Remi hunt for lumen caves, and splitting the rights with them on any new ones they find. It’s not clear why Eda is looking for them, but all that’s on Jun’s mind is restoring his clan to its former greatness.

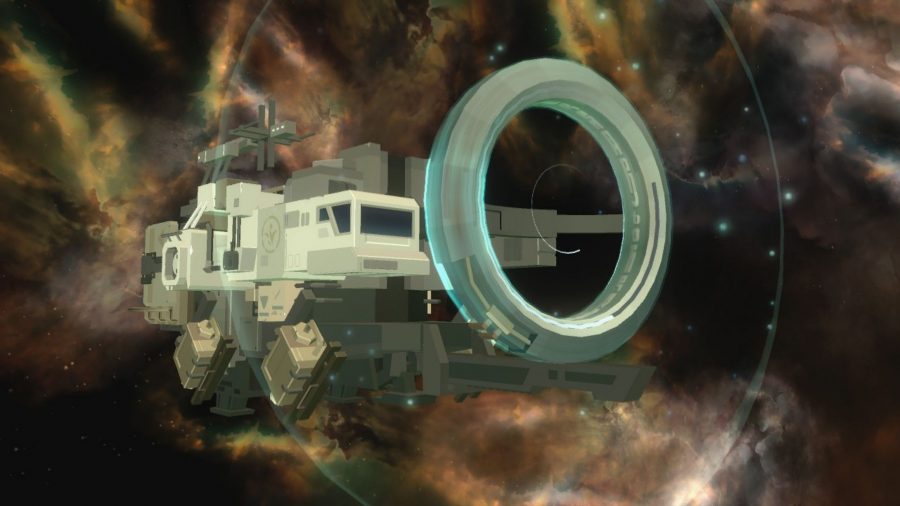

The gameplay is multi-faceted. On an overworld map of different space stations and caves, you choose new destinations to analyse and discover. In order to travel you need fuel, to get through conflict you need armour plates, and to explore you need exploration kits. On the populated space stations there are numerous people to meet, unique vignettes to see, and the ability to trade. To keep exploring, you need to trade things you find for the above essentials.

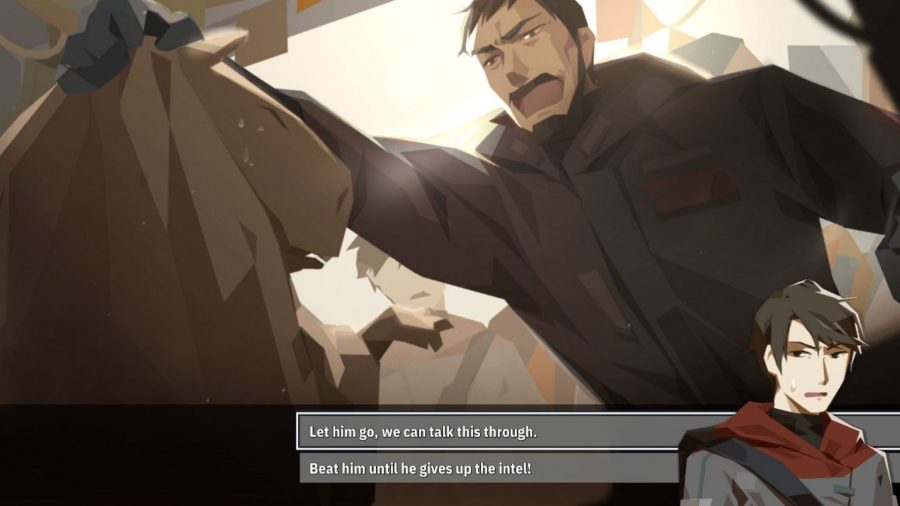

When travelling between points of interest random events often occur – a dodgy bunch of pirates masquerading as civilians in trouble, a news reporter looking for a scoop, for example – and the outcome of these events is based on a kind of dice roll system. Do you just keep going past this nasty pirate ship and hope they don’t blow you to smithereens? Go ahead, you’re probably going to get shot. Or do you try to trick them by sending a signal from the Red Chamber to masquerade as an ally? That’s when the dice roll happens.

You can modify this dice roll by upgrading your ship’s capabilities or the characters’ luck. The higher Eda’s luck, the more likely she may be able to talk her way out of a tricky situation. The better the ship’s signal modifier, the more likely it is that the signal will fool the enemy, and so on. This is the resource management aspect of the game, all of which is key to exploring the stars.

You don’t just explore on the macro level though. When you reach lumen caves, the game becomes a puzzle side-scroller. You go into these caves, pick up different plants to sell later, and also unlock gates to discover the secrets within. These gates rely on lumen, with numerous inactive pipes needing to be connected altogether which can be activated with a starsong.

Starsong is something that can resonate with lumen. Creating different sounds can open gates, while the lumen itself can also resonate back, helping people find it, as long as they have the ability to resonate with the lumen themselves.

If you have the right starsong, Jun can use it to activate the pipes, which then allow Jun to open the gate. He does this, again, by using starsong to solve a little puzzle involving finding the right frequency to connect with the gate. If you don’t have the right starsong, Jun can distil a starsong from a pool of lumen with his synthsceptre (a sort of starsong conduit), or Eda can create recordings of a starsong with her voice. Jun opening the gate or Eda creating a starsong involve separate puzzle minigames that are simple but effective.

So, by my count, we have about a billion different mechanics here, all of which sound quite banal when explained plainly. But the way they all work together is wonderful, making every aspect of the game feel like you’re involved. Whether you’re exploring the stars or a tiny cave, you have to make decisions. The puzzles are never difficult, and connecting up lumen pipes in a cave can very occasionally become tedious, but for the large majority of the game, I was engaged. There’s a tension before every decision, every dive into a new lumen cave, every low-armour cross with a ship of pirates.

The game is beautifully realised too, both visually and aurally. The sound design is exquisite, whether it’s the crack of Jun’s synthsceptre or the rattle of the Red Chamber, engrossing you deeper into this strange version of humanity. Then there’s the soundtrack, changing depending on your destination. The lounge jazz of a casino, the ambience of a desolate cave, or the rising synth of a moment of beauty – everything is pitch-perfect.

I was also blown away by the art at many points. Story moments are brought to life with excellent character art. This extends to your travels, too. As you pull into a new place, the art sits, briefly, without any menu options over the top. There are bustling space stations, bright and volatile stars, asteroid belts, and ancient structures, all presented in a way that creates genuine wonder. It feels like discovering something.

All of this serves as an excellent foundation for a decent game, right? Lots of fun stuff to do no matter where you are, lots of pace changes to the gameplay – from the slower, more involved cave exploration, to the quick little starsong minigames – and all in all a wonderful set of things to get on with all presented beautifully. That’s true, for sure, so what makes Echo of Starsong special?

That’s where the narrative comes in. In Echo of Starsong, the story hits hard throughout, whether it’s treading over simple backstory or serving up a heartrending twist. Just like the exploration working on a macro and micro level, the story works in terms of large scale narrative, interpersonal story arcs, and the tiniest, individual moments, all through the memory of our narrator, old Jun.

Jun pines for the good times, trembles at the bad, and, of course, never feels wholly reliable. At first, it seems like Remi is just abusive to him with no real motivation. It seems like Eda switches from cold to warm like the flip of a coin. But this unreliability allows the narrative to blossom in its own, natural way.

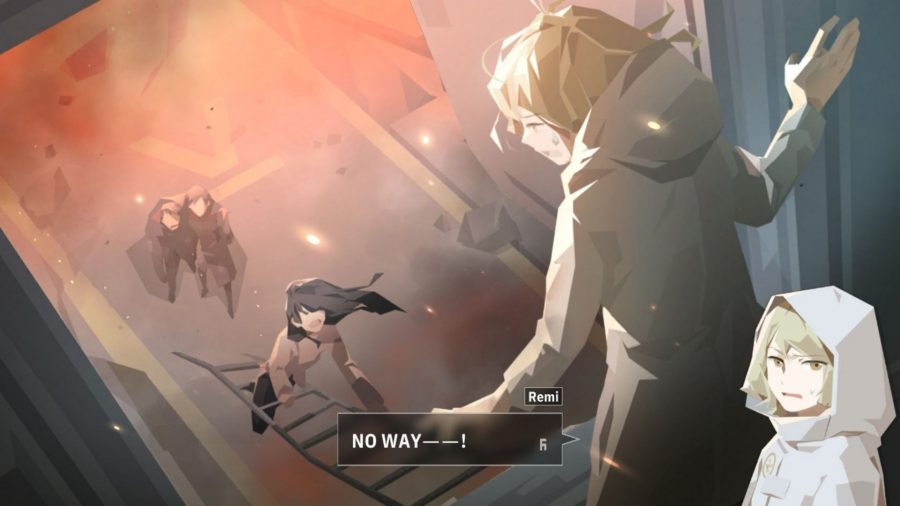

You learn a bit about Remi’s past about halfway through the game. It explains so much about her relationship with both Eda and Jun, and feels all the more heartbreaking to see, as the game lets the audience assume she’s just a bit of a brat. These flashbacks dot the narrative constantly, and the deeper you get, the more powerful they become.

This is the centre of the three layers of the narrative, the relationship between those three characters. It’s not just seeing sad bits of their past that makes it work, though, but also the fact that the game deploys these moments at just the right time. They come when they’re needed, and when they’ll make the most impact. The game is happy to hide so much from you, only letting you come closer to the characters when the time is right

This helps them develop naturally, and gives Jun, Eda, and Remi clear arcs. Their personalities don’t change dramatically, but the context of their actions and reactions does. The more you get to know the characters, the more context you’re given for everything they’re doing. It lets you develop sympathy for them over time.

The lore of this world is where the larger storytelling happens, the outer layer. Through various items collected, inscriptions on cave walls, and tidbits of chatter, we get the cosmogony. Whether it’s myth or fact is unclear, and it doesn’t really matter. Many strangers make a lot more sense thanks to the opaque nature of the world’s history.

There’s also large-scale space politics, with numerous organisations all working for their own gain. The fact that these large factions have broad personalities helps you assume things about the characters you meet based on their affiliations, but also lets your assumptions be broken by the writers in clever ways.

Then there’s the inner layer of the three ways the game tells its stories. These are the various encounters with high ranking officials, nasty corporate soldiers, amputees from the Lumen War, and many, many more people. You probably talk to them for no more than a minute, but they leave an impact. It just comes down to good writing which helps these characters all feel like real people, reacting to real things in the world. Once you learn the rules and history of Thousand Peaks, your brain can construct a quick imagined backstory, if need be.

This game also has a wonderful, subtle kindness in its narrative. While it’s coated in old Jun’s melancholy and full of all manner of scoundrels, the game rewards you for trying to do the right thing, and you see most of the other characters getting rewarded if they’re good people too. It’s not some grand, moral statement, but just subtle things here and there – a small trinket from a beggar you gave money to, a handful of coins for helping people get through a load of debris in space, for example – that make it feel like you can do some good in this harsh place.

This world appears to have the right balance, and so do our three main characters. They may have their bad sides, but they all seem to have good intentions. This heart helps the narrative become very close to you. I feel sincerely close to Jun, Eda, and Remi. I care about them, so I care about my decisions. But I wasn’t role-playing them, I was making decisions both because of them and for them.

It’s a symbiosis between me and them, between my agency and their intentions. I felt like I was shaping the crew of the Red Chamber over years, even if it’s completely pre-ordained by the narrative. Just my agency in the various gameplay decisions, whether choosing to head to an abnormal signal or deciding to explore an ominous lumen cave, made the story my own, even though this isn’t a role-playing game.

I want to help the narrative go in the optimal direction with every decision I make, doing what’s best for the characters. But I also make decisions based on what I think they would do. Not just what I think they should do, but also how they would actually act.

This back and forth between me trying my best to make everything work and the characters getting in the way is where the power of the narrative explodes. You can feel so in charge, yet still get it wrong. You know where Jun ends up, as he’s telling you about everything, alone, in a desolate place. But you still want to avoid it. And the more you play, the more convinced you become that you can do it.

This sidesteps the problem narrative games have had forever in a really simple way. How do you make an authored narrative where the player can make decisions, and still have it satisfying through to the end? It’s really hard, but Echo of Starsong does it by showing us the end throughout (and by having an excellent story). You never forget that you can’t change it, but you feel like you can try your best. The writers get to create the story they want to, and the player gets to feel like they’re the one who wrote it.

So, can a computer make you cry? Well, yes, we already know that, but also, who cares? The more important question is how deeply can videogames affect you? How long can they stay with you? Game narratives are still moving forward, in ways that are so genuinely exciting. And not just in sheer quality, but also in the way the narrative and the gameplay intertwine. Opus: Echo of Starsong does both – it’s a story of such a high quality told in the best way possible.