Our Verdict

Pacific Fire is a surprising hidden gem. It has some shortcomings, but is overall an excellent use of your time.

A strange thing that occasionally happens to me is that I get what I’ve referred to as Paradox dreams. Not because they are self-contradicting, but because they occur when I play too much of one of Paradox’s grand strategy games, such as Crusader Kings 2 or Europa Universalis 4.

Essentially, my brain ends up thinking of ways I can improve my position in these games via my dreams. Pacific Fire has gotten my attention in such a way that I had one of these ‘Paradox dreams’ about it. So, what’s so special about this mobile wargame that it has kidnapped my subconscious?

Oh, before we move on, why not check out a few more examples of the genre in our best mobile war games list?

Pacific Fire does not have much in the way of astounding graphics like you may see from AAA mobile studios like the big brains behind Clash of Clans or Candy Crush (people still play that, right?), or a very engaging story, but neither are really missed. Pacific Fire knows what it is good at, and has cut everything else in favor of compelling and engaging gameplay.

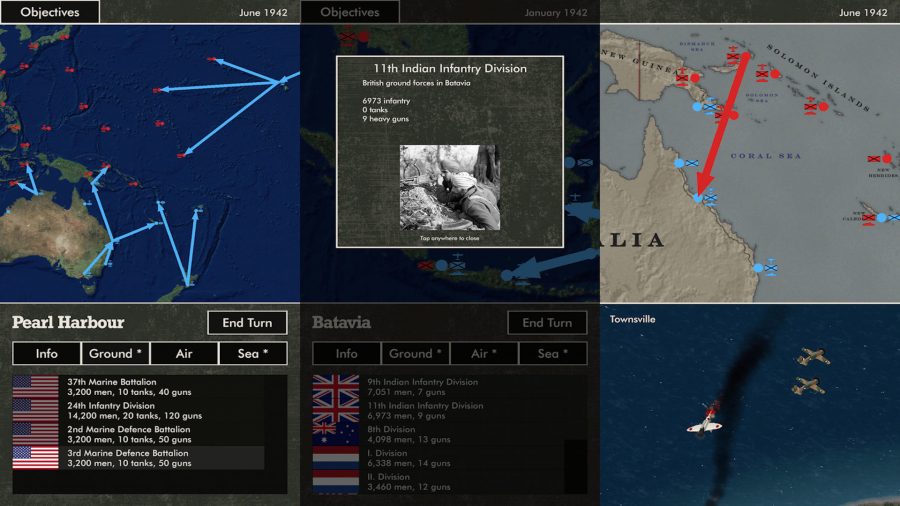

You are given several scenarios to try your hand at, pushing air, land, and sea units between bases in order to complete your objectives for the scenario, generally on a strict turn limit of x amount of months.

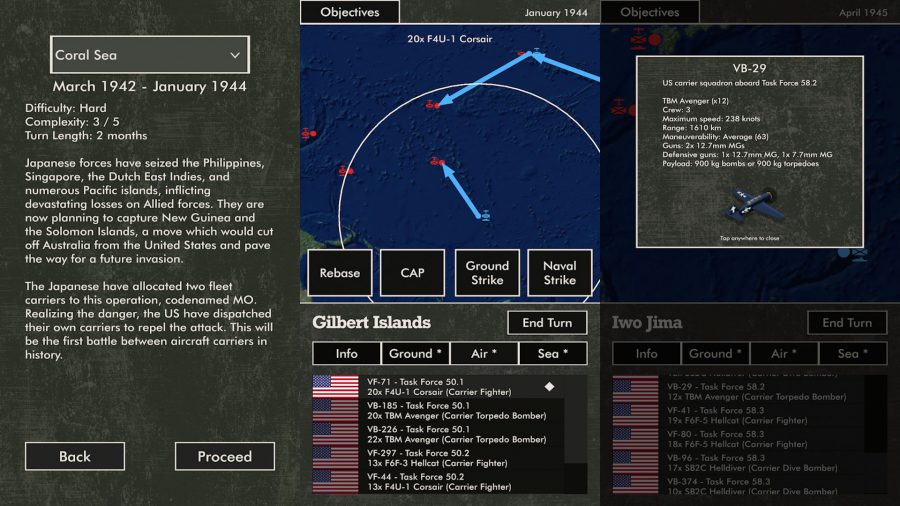

Notably, the game uses WEGO, a turn method that sees both sides make their moves simultaneously, then showing how the action played out at the beginning of the next turn. This format suits Pacific Fire wonderfully, as the Pacific theatre’s naval engagements were defined by the opposing fleets guessing the other’s position, attempting them to coax them into a decisive battle on their own terms.

This brings us to the most important element of Pacific Fire: the order in which all these moves take place. There’s a grand total of fourteen steps to combat resolution, but essentially it boils down to this: air units arrive at their destination and dogfight with enemy air units, the surviving bombers attack their respective land or naval targets.

The naval forces then move to their destination, fight the enemy naval forces, and bombard any land units. Lastly, land units resolve their combat with the enemy. This turn ordering allows for clever strategists to replicate the great naval battles of the Pacific, with smartly deployed squadrons and fleets able to negate an invading army’s numbers.

In a nice touch, planes and ships have their own sets of stats, which determine how they function in battle. Generally, newer vehicles operate at a higher efficiency. On a similar note, land units have three stats that determine combat capability: men, tanks, and guns.

Men are the overall strength of the unit, tanks help the unit in offensive battles, and the guns help on defense and help protect the unit against enemy bombers. This layer of attention to units adds a degree of thoughtfulness to how you should utilise your army, making successful actions pleasing to pocket generals. (Consider yourself a pocket general? Check out our list of the best mobile strategy games then.)

That’s all very well and good, but what about the context surrounding these engagements? Pacific Fire comes with a total of 13 scenarios (1 of which also operates as a tutorial), with a focus on specific areas of the war. There are several scenarios from the Allied side that capture the struggle to survive as war broke out and the Japanese overwhelmed the British, French, Dutch, and American holdings.

These make for good starting scenarios, as the map is smaller, and the Allied player needs to worry about deploying smaller numbers of units rather than the entire Pacific theatre. Even while these are certainly scenarios aimed towards a beginner, Pacific Fire is not an easy game. Leaving a base without fighters to defend it can see enemy bombers quickly killing hundreds of men, leaving the player in an unwinnable position for the scenario.

The scenarios covering the later parts of the war are generally more challenging, including a particular campaign covering the time period around the Battle of Coral Sea (still haven’t managed to beat it). Even more intimidating, there are 3 full Pacific campaigns available, with increasing complexity and difficulty. While several scenarios can be wrapped up over the course of a lunch break, these will be campaigns that take a longer stretch of time.

Disappointingly, there are less playable scenarios for the Japanese, but these are very interesting scenarios. One follows the Japanese in the Burma campaign, looking to push into China and India with zero naval forces (a companion to the much harder Allied version of this campaign). Another notable scenario uses the “What If” of an invasion of the Japanese home islands, using civilians to hold off the Americans until a peace can be brokered.

The Japanese don’t play significantly different to the Allies, but there is one key difference. Both sides in a scenario have an “Industry Score” that determines how many reinforcements will be deployed at the end of the turn. The Allies gain Industry Score over time, but the Japanese player’s score depends on how many bases they hold. As they control less territory, the Japanese are less able to replenish their forces, which follows the “rules” of the history well.

While Pacific Fire does a lot right, the few flaws it has are amplified by the focus that is placed on the gameplay itself. In some of the smaller scenarios, it’s easy to feel as if there is a “right” answer to unit movement and placement, making these scenarios feel more like puzzles than proper warfighting. This may not be an issue to all players, but for a game that has several solid wargaming scenarios, these can be disappointing, as one wrong move can mean that a win is impossible.

Similarly disappointing is that with a lack of multiplayer support, the game is entirely player v. AI. The AI is… interesting. It’s difficult to realty get a feel for it, as the AI deciding to sit on a base for several turns without moving could either be a cog in a larger strategic plan, or it could be the AI not properly utilizing all of its forces. It does seem easier to lure AI naval fleets into an engagement than it does to bait an army to attack, but that may be just contextual.