During one of the GDC 2020 sessions I was lucky enough to catch Yuichiro Tanabe’s talk about creating the art of Sky: Children of the Light. Tanabe is the lead artist at thatgamecompany, and during his talk he explained the fundamental layers surrounding the creation of Sky’s six in-game levels. He also went into depth on how the art team designed Sky’s iconic ‘children’ – the angelic characters you inhabit when playing the game. As a huge Sky fan, it was honestly a real treat!

Tanabe began by discussing the core design philosophy of thatgamecompany – to ‘connect players worldwide through positive emotional experiences’. He also discussed the company’s previous games, including Flow, Flower, and of course, the hugely successful Journey.

Journey, Tanabe said, is “a spiritual predecessor” and much of Sky: Children of the Light’s message centres around trying to build upon the same feeling of emotional connection that many players experienced with Journey. Tanabe then proceeded to explain the three core layers that inspired the creation of Sky: Children of the Light’s environments and characters

time of day

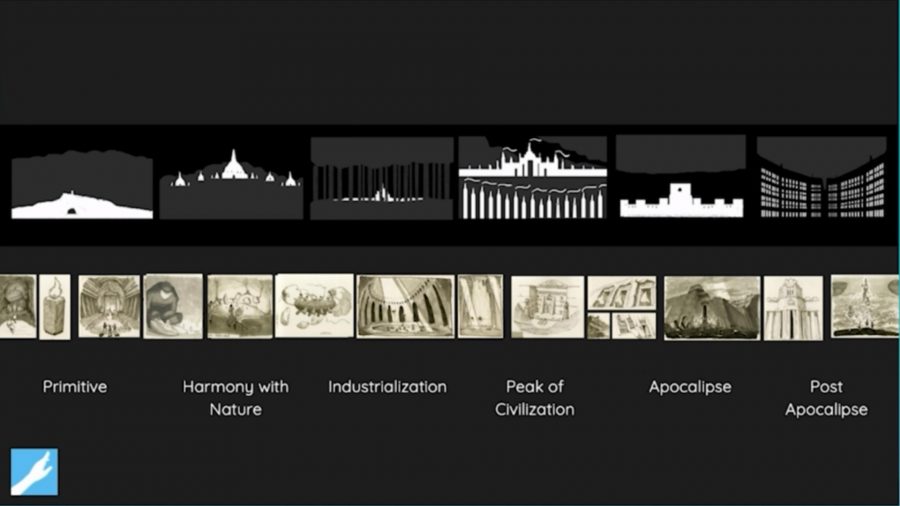

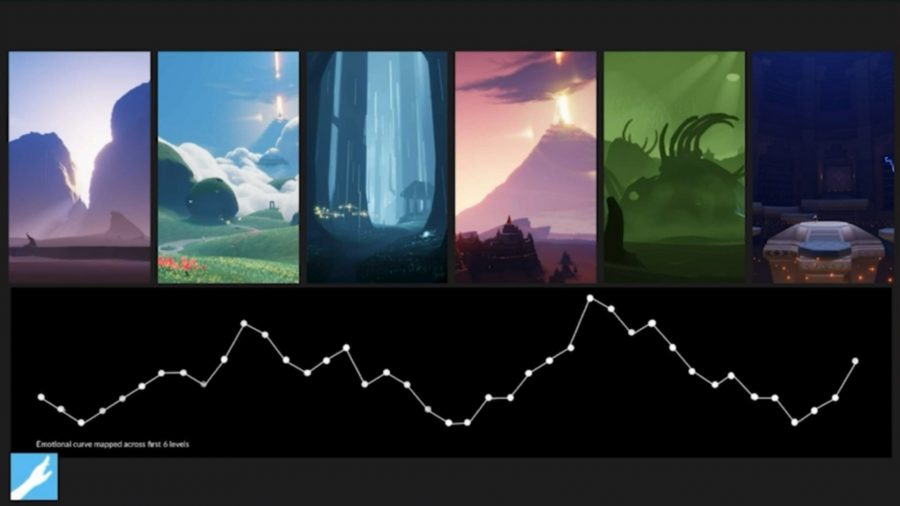

The first layer of Sky: Children of the Light is ‘time of day’, and each of Sky’s six levels represent a different weather and time state. From left to right it goes: morning, day, rain, sunset, dusk, night. This progression of states allowed for a mapping of Sky’s emotional narrative, which Tanabe explained is somewhat reminiscent of ‘Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey’. This progression can be seen mapped below the images.

It also allowed Sky’s artists to create lighting and world elements based around these states. For example, the Valley of Triumph, pictured fourth along, represents sunset, ‘a dramatic, magic hour’ and this is reflected in the level’s lighting and the exciting race that occupies half of it.

human life

The second layer of Sky is ‘human life’, and just as the levels follow an emotional journey, so too do they mirror a human lifespan. Each level represents a different stage of human life: birth, childhood, adolescence, maturity, midlife crisis, and elder. The Hidden Forest for example, pictured third for the left, features rain, more complex level design, and emotionally complex gestures, so as to reflect the struggle of adolescence. The Isle of Dawn, on the other hand, is empty and expansive, representing ideas of beginning and birth

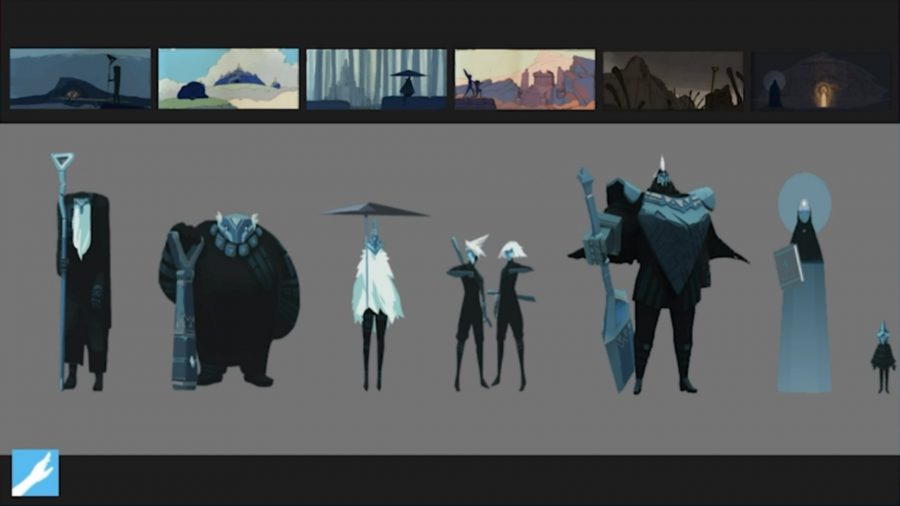

Even the characters you meet in each area, and the gestures they teach you, are based around the level of emotional complexity occurring during each period of your life. The elder spirit characters are also modelled upon these periods – the old looking spirit on the Isle of Dawn depicts how aged a regular person might look to someone who’s just been born, whereas the twins in the Valley of Triumph depict the ‘competitive nature of adulthood and maturity’.

progression of civilisation

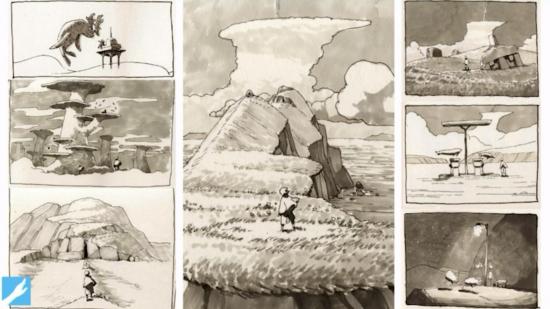

The third layer of Sky is the ‘progression of civilisation’, and just as with the two previous layers, it is also mapped to Sky’s six levels. As you can see below, this timeline helped inspire the architecture of each level, whether it’s the grand, excessive structures visible in the Valley of Triumph – third from the right – or the ruined industrial remnants of the Golden Wasteland – second from the right. Tanabe didn’t elaborate, but perhaps this timeline also gives us a clue as to the actual journey of Sky’s in-game civilisation

creating sky’s children

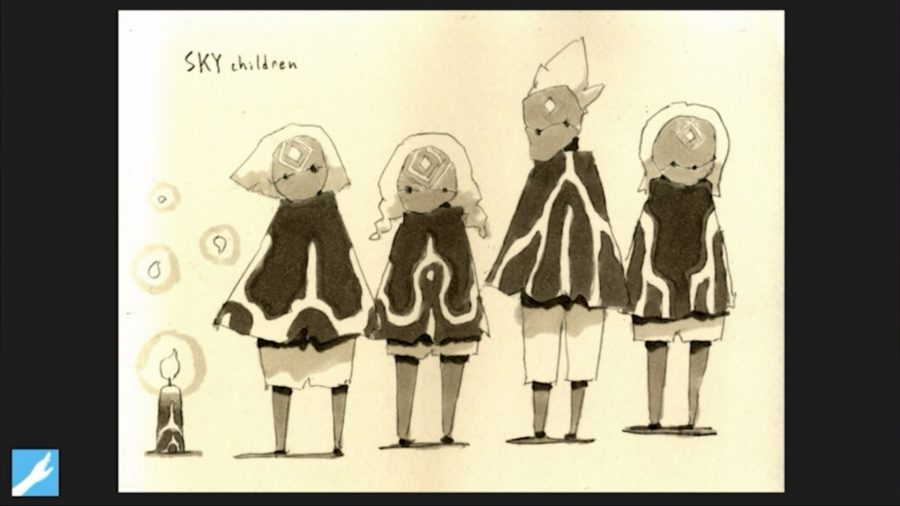

From the beginning, Tanabe explained, thatgamecompany knew Sky was going to be a game about flight, community, and emotional connection. The game is supposed to represent the idea that “everything is better with others”, so when designing the player characters, these considerations were prioritised. It was decided that Sky’s characters would be children to highlight a sense of vulnerability, and this was also what decided the signature winged poncho that every Sky child wears.

The masks were chosen to eliminate the difficulty of expressions, as was the white hair, which is intended to take away any impression of specific race. As Tanabe explains, Sky’s cosmetics are ‘a canvass’, and it’s easy to see the balance that Sky’s children strike between being blank enough for us to project onto, but not so much as to be expressionless. Journey’s character design was based around in-game functionality, and it can be seen in the main characters lack of arms – Sky’s children follow a similar design philosophy.

It was a great talk, and it really made me realise how all the varying elements of Sky’s game design work to compliment each other – a single emotional curve running throughout the whole game. The talk concluded with the advice that “if you’re ever in doubt, remember the message you are working towards and follow through”. Though Sky is such a unique game experience, its ideas of vulnerability, community, and emotional connection resonate with players of all ages throughout the world, and in the end, as Tanabe reflects, that’s every developer’s true reward.

Be sure to stayed tuned for more GDC coverage! Also if you want to play the game for yourself, we have a handy Sky: Children of the Light guide to help you get started.